How is the ACL torn?

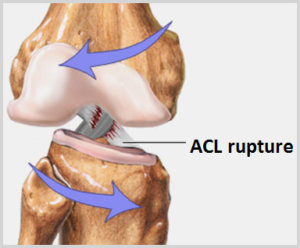

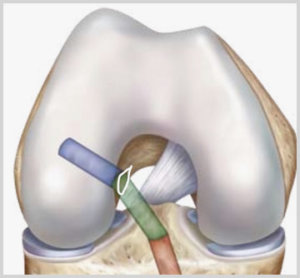

The ACL tears when it is stretched beyond its ability to resist. The mechanism of injury may be a direct blow to the leg (eg a rugby tackle), a sudden twisting movement either during a fall or while trying to pivot on a planted foot (a classic netball injury), or by hyperextending (over-straightening) the knee.

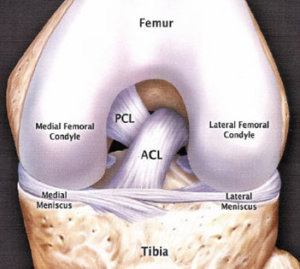

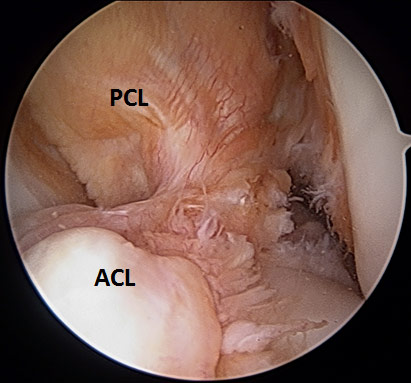

Depending on the force and direction of the injury, the ACL can either be partially or completely torn. Other structures within the knee can also be injured. The menisci within the knee, other ligaments, such as the collateral ligaments and the articular cartilage are all at risk.